“Conservation and Demolitions. Memory and Oblivion”

Authors:

Miguel A. Calvo-Salve, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania, USA

Maria N. McDonald, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania, USA

Russell B. Roberts, Marywood University, Scranton, Pennsylvania, USA

EAAE - NETWORK ON CONSERVATION. WORKSHOP VII - PRAGUE- pages 346 – 357

Introduction

Conservation of the built heritage has seen an increase in the number of cultural values to be preserved and growth in the number of elements of listed architectural and cultural heritage. In the last several decades, UNESCO and ICOMOS have been identifying all those aspects of our cultural heritage that must be preserved, authenticity and identity, the tangible and intangible cultural elements, and natural landscape. The number of agents involved in preservation and conservation actions have increased, therefore, along with professional and public awareness. Due to the increase of listed heritage and values, and amenity groups, conservation of our cultural heritage needs to address more threads than in the past and to cover a wider range of actions and scales, from individual to collective, cultural to social, and material to immaterial.

During the recent EAAE Network on Conservation Workshops, we have discussed many of the topics and threads that the discipline is facing, including how the increase in tourism is overwhelming the listed heritage, concerns regarding the adaptation of protected structures and buildings to new uses, the dilemmas facing the reconstruction of buildings and sites due to natural or provoked catastrophic events, regeneration and transformations, and the importance of teaching goals and methods. In the 2019 Workshop held in Prague, the thread addressed was the intentional destruction of sites or buildings, including their partial or total demolition, and how it affects individuals and their communities.

The agents involved in conservation always face the dilemma of whether to preserve, adapt, transform, or demolish an historic building or piece of urban fabric. They must consider all material and immaterial components, the use of modern technologies in construction systems, the incorporation of new solutions and materials, while understanding the commercial forces that historic heritage faces in terms of consumption, the risk of “musealization”, the interest in providing a meaningful use of the preserved historic construction, and the implications at different scales that the specific architectural element has.

The topic of demolition within the discipline of conservation also presents multiple dilemmas to the agents involved, not only when addressing historically recognized architectural sites, but also in the historical urban fabric that has configured specific life events around them, and the sites and their context that have faced damage caused by abandonment or other economic or political events.

Destruction and Demolition as part of the Historical Built Environment

In thinking about demolition and destruction, we must not forget, as the philosopher and literary critic George Bataille stated, «we cannot ignore or forget that the ground we live on is little other than a field of multiple destructions» (Bataille 1988: 23) . It was human action in the pursuit of shelter, dwelling, development, financial status, building communities, and power among other reasons that created our built environment. It is those elements of the built environment that claim to have cultural and historical value that we demand to be protected.

Historically, the demolition of structures, buildings, urban blocks, and neighbourhoods has been part of the renovation of cities since medieval times. Haussmann’s renovation of Paris demolished numerous eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings and blocks of the medieval urban fabric, because of the overcrowded and unhealthy conditions of the buildings. Instead of acting on those buildings and blocks to improve the living conditions for their inhabitants the decision was demolish them. Haussmann’s plan was not executed without critics at that time. Patrice de Moncan in his book Le Paris d’Haussmann, mentions the loss of Paris’ picturesque presence by quoting French writers like Edmund and Jules de Goncourt or French politicians like Jules Ferry that deplored the demolition of parts of old Paris that had played an important role in the writings of the novelist Honoré de Balzac, the philosopher and writer Voltaire or the journalist Camille Desmoulins (Moncan, Heurteux 2002: 198-199). Indeed, de Moncan argues that the Haussmann plan created an important social disruption, by demolishing medieval housing and relocating those families to the outskirts of Paris. It resulted in a dramatic increase in rents in the renovated areas that forced those low-income families to stay in the outer arrondissements, on the edges of the city, which is what we nowadays call a gentrification (Moncan, Heurteux 2002: 172-173).

Similarities can be seen in other examples - the creation of the Plazas Mayores in numerous medieval Spanish cities such as the Renaissance Plaza Mayor of Madrid, or the Baroque Plaza Mayor of Salamanca listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, or the opening of the Gran Via in Madrid in the beginning of twentieth century. These historical urban interventions involved the demolition of parts of numerous medieval cities to create the orderly layout of the large open space of the Plazas Mayores within their irregular and crammed configurations.

Numerous current plans for conservation of historical cities in Europe allow for the demolition, or “gutting”, of the interior of buildings for their complete renovation or adaptive reuse, while keeping the external facades. Historic buildings become little more than carcases of their former functions after large renovation campaigns in those historical villages (Crinson 2005: xi). New interiors behind those saved facades, such as museums in old factories or new commercial spaces with the mask of a medieval facade that were once dwellings for city inhabitants, can create a loss of collective memory within the community and lead to an identity crisis.

Demolition and Memories, Oblivion.

In the last decades, the concept of memory has become of special interest for some historians, exploring the social dynamics and the experiential aspects of social processes, oral history, and the representation of the past. In Maurice Halbwachs’s seminal book On Collective Memory, he points out that it is in society that people acquire their memories and also in society that they recall and organize their memories, binding the people together, frequently referencing their memories to their physical spaces, which creates a moment in which collective identity is formed (Halbwachs 1990). These links between memories, places and communities are evident in Joseph Rykwert’s book Remembering Places. The author of many influential books on architecture, wrote his memories with continuous references to their physical spaces, buildings, neighbourhoods, and cities as well as to the societies and communities to which they belonged (Rykwert 2017). Aldo Rossi made clear references to urban contexts when he argued that the memory of the city is in its buildings, referring to the collective memory of its inhabitants, which allows them to identify and follow the traces left in the city. Disappearance of those traces or buildings can lead to memory loss, and to cities losing their collective memory of its form (Rossi 1984: 130).

During the recent past, there have been important issues raised concerning the post-industrial city and contemporary urban forms based on the relocation of industry. During the twentieth century, many countries have experienced the process of dismantling and remaking of industrial cities as part of capitalist investment practices. Those processes were aimed at the introduction of new functions, transformation, regeneration, and restyling, included a process of gentrification.

In the first half of the twentieth century, New York City saw an important process of demolition of city memories. Max Page in his book The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940, described how many slum clearance projects, created to improve the physical environment and offer amenities and services for low income citizens, resulted in the destruction of those areas considered “unhealthy” for the city, but which were of financially interesting for the government and private sector elites (Page 1990). The protection of Greenwich Village in New York City by Jane Jacobs in the 50’s and 60’s is well known. Jacobs clearly understood the “organized complexity” of neighbourhoods that have a mixture of building uses, in which residential areas are combined with industrial facilities, promoting a diversity of population (Jacobs 1992: 428-455). She used the Village as the best example of a functioning, vibrant and diverse city neighbourhood in arguing against Robert Moses urban renewal projects, which demolished large existing urban areas, and transformed those neighbourhoods using the modern model of isolated residential buildings and segregated uses, such as was done in Stuyvesant Town, that has now been discredited.

Max Page, in the above-mentioned book, references Halbwachs when addressing the destruction and rebuilding of parts of Manhattan, saying «How can spatial memories find their place where everything is changed, where there are no more vestiges and landmarks?» (Page 1990: 252). The co-dependency that memory and the physical environment of buildings or landscapes creates has been lately studied and explored by historians. Recall of those memories is often seen as an example of intangible heritage in a social and cultural context, containing values for conservation practices. Addressing the memories of places as heritage also brings the addition of collective and social values to historic and aesthetic elements that are usually controlled and only addressed by professionals in the field of heritage.

A city’s memories and traces linked with its inhabitants were evident during the EAAE Network on Conservation visit to the neighbourhood of Holešovice in Prague, a heavy industrial and mass-housing suburb in the north of Prague, located on the west bank of the meander of the River Vitava that was developed during the end of the nineteenth century and the first quarter of the twentieth century. During the last several decades, the Holešovice district has seen the renovation and adaptive reuse of its former slaughterhouse into the Prague Market (Pražská tržnice) (fig. 1) which also houses art galleries and an international performance space; the transformation of the former Rossemann and Kühnemann machine, wagon and locomotive factory into the Dox Centre for Contemporary Art; the conversion of the industrial buildings of Ritcher Machine Works and Foundry into La Fabrika multifunctional cultural centre; and the transformation of VNitroBlock, an former industrial complex, into a social, cultural, and shopping creative centre (fig. 2). Some of the residential blocks built during the first quarter of the twentieth century in Holešovice have been renovated as well with insertions of new contemporary residential construction (fig. 3). Large areas of numerous blocks have instead been demolished and will be redeveloped into new condominiums and large offices buildings. The district seems to be fighting to maintain its past identity and recover its memories, while an important process of gentrification is occurring, and both the government and private developers with economic and financial interests are taking advantage of the situation.

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur identifies in his book Memory, History, Forgetting, the erasing of traces as one of the most important aspects of forgetting at a “radical level” (Ricoeur 2004: 414). Different obscure interests throughout history, from political to financial and social to cultural, have driven those processes of effacement of traces of what might be call the burden of memories. The debate about and practice of conservation and intervention in heritage raises identity questions related with these processes. What are those traces of the past that sustain memories of the place? What do we select to remember or forget? What do memories and oblivions tell us about specific places?

Two Cases in Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.

A short editorial in The New York Times addressing the demolition of the Penn Station in New York City in October of 1963, it reads «we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed» (NYT 1963: 38). The demolition of the emblematic and beloved train station sparked a debate about the dynamic of the destruction of buildings in the United States. It also brought well known modern architects and historians to action. The architect Philip Johnson and historian Lewis Mumford among others, were seen in front of the train station holding placards in favour of its conservation and against the demolition (Byles 2005: 142). This debate in the United States is still going on, where The National Trust for Historic Preservation complained at the beginning of the twenty first century that «a disturbing pattern of demolitions is approaching epidemic proportions in historic neighbourhoods across America» (Fine et all 2002: 1).

The city of Scranton, in the Northeast of Pennsylvania, has been a one of the numerous medium size cities in the United States of America that have seen his built heritage neglected and wrecked. During the end of the ninetieth century and the beginning of twentieth century, Scranton was one of the greatest industrial and coal mining cities in U.S.A, leading in the manufacture of heavy hardware and textiles, with a vast railroad network, and with the nation’s first electrified trolley system (The Scranton Board of Trade 1912). By the mid-twentieth century, the city of Scranton had a population of 140,000 inhabitants. After World War II, the turn from coal to oil and gas for heating fuel marked the start of a process of decline in the manufacturing, transportation, jobs, and population that lasted for six decades. Industrial buildings and commercial buildings in the downtown area were progressively abandoned. What once was a vibrant city was transformed into a ghost town. As mines were abandoned, cave-ins and massive fires in culm dumps resulted in the suggestion by 1970 that it might be more economical to abandon the city than to make it safe.

The last quarter of the twentieth century brought an increased interest in the revitalization of the city, that the journalist Jane Jacobs, the author of the book The Death and Life of Great American Cities who was born in Scranton, recognized in a visit there in 1984. While some historic properties have been renovated, and some transformation has occurred, neglect has also led to the demolition of important historic urban fabric.

In April 6, 1992 the Headlines of Scranton Times Tribune read «Scranton Demolishes Buildings to Make Way for New Mall Buildings in Scranton Blow Up. $101 Million Mall to Rise from the Rubble». The City of Scranton did in fact implode the 200 and 300 Blocks of Lackawanna Avenue in the heart of its downtown. They quite literally blew it up. What was once called “The Great White Way”, because of all the lights that illuminated the buildings at night, was erased in a matter of minutes (fig. 4). It took just one quick flash; five loud bangs and the buildings fell like dominoes in succession (fig. 5). Onlookers stood and watched in wonderment. Some were cheering while others were crying. It was a traumatic event from which the City has never fully recovered. The memories of the once bustling city had been sacrificed for progress. «I am watching History disappear», said one shop owner (Salter 1992). In its place, a sparkling new suburban shopping mall was to be injected into the fabric of its City Center and was sold at the time as the start of Scranton’s “Second Renaissance”.

One of the onlookers, who wasn't on the street that day, but who was certainly watching from a distance, was Jane Jacobs. On December 31, 1987 Jane wrote a letter to Mr. Tim McDowell, Director of Scranton’s Office of Economic and Community Development. This was during the Mall's early planning. The Letter opens with complimentary language: «Dear Mr. McDowell, on a visit to Scranton in 1984 I was struck with how visually attractive it’s downtown had become and at the many visible signs of vitality and prosperity» (Jacobs 1981) [1].

In her letter, Jacobs continues pointing out the many handsome old buildings which have remained and further praises him for the City's resurrection from the Great Depression. She then expresses her concerns and backs them up with a series of explanations as to why the proposed Mall is a “terrible” idea. She predicted the future. Everything she said in the rest of the letter came true: «However, now I am appalled to hear that there is a proposal to level an appreciable section of the downtown on one side of Lackawanna Avenue and to erect, of all things, a suburban-type shopping mall. Far from enhancing or strengthening Scranton’s downtown, a mall development is guaranteed to be destructive economically, visually and socially» (Jacobs 1981).

Jane closes her heartfelt letter with a plea for her First City Scranton which in fact is her hometown. «Why is an outsider like me being so officious as to send you advice you haven’t solicited? Two reasons: First, I hate to see gratuitous destruction visited on any city and more so when the city has so much going for it that is beautiful, admirable, and promising. Second, I am not entirely an outsider. I was born in Scranton and brought up in Scranton and Dunmore. … I have felt sad when Scranton fell on hard times, have rejoiced to see it prospering and turning weakness to strength, and feel vicarious pride when I hear others admire the downtown I admire. I only hope that you respect what Scranton is, has been and can be» (Jacobs 1981).

The recent discovery of this unpublished letter from Jane Jacobs in the archives of the Architectural Heritage Association in Scranton, brought back temporally people’s memories of the traces of its downtown historic fabric that fell into oblivion. Today the SteamTown Mall now sits mostly empty, has wreaked havoc on the downtown economy, and it is visually out of step with the remaining Historic Buildings, making real Jacobs’s predictions. Now, some of those architecturally significant buildings are being transformed into loft-style apartments, while others are being demolished and rebuilt as replicas in a style that tries to mimic their original splendour.

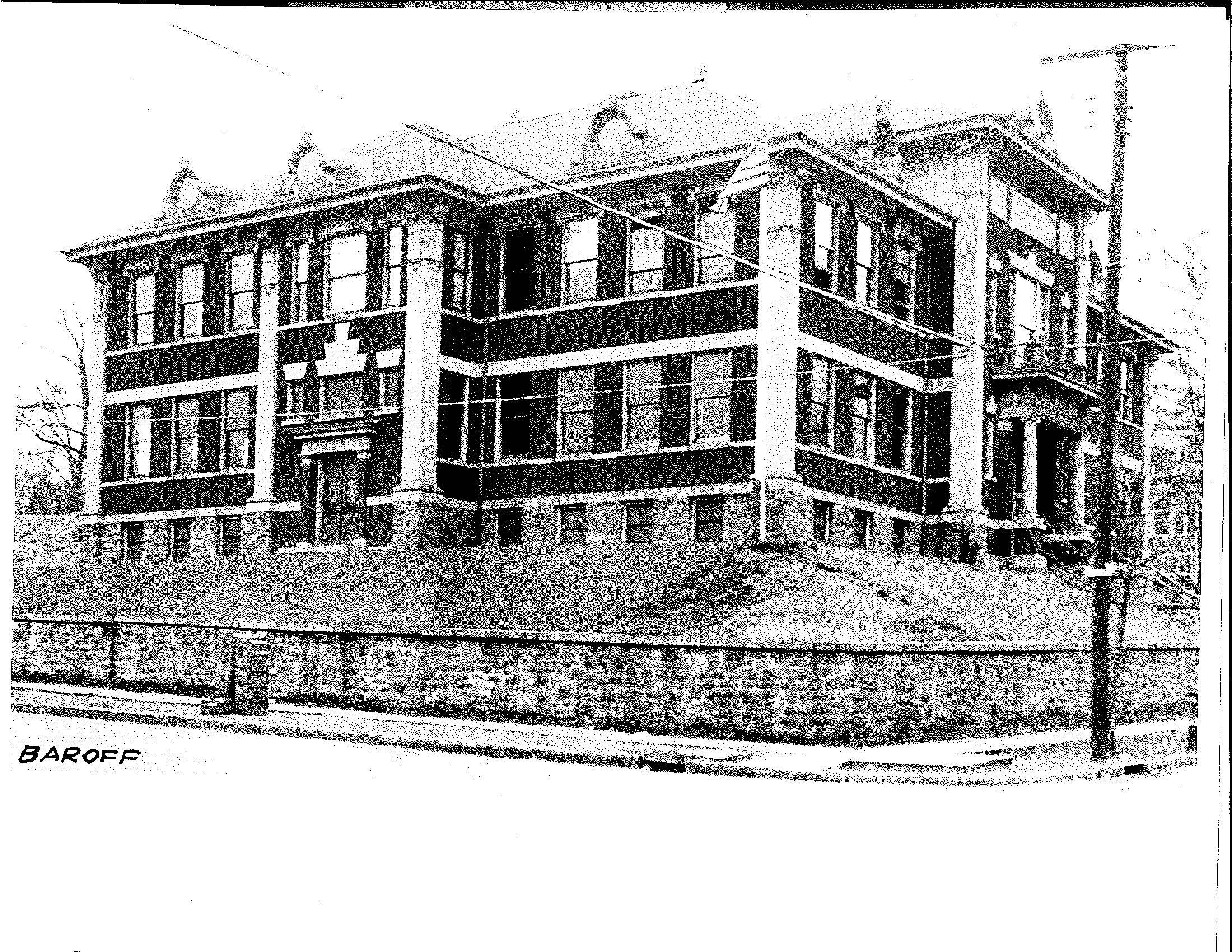

The outstanding industrial heritage of the city of Scranton has been also affected. One of the largest industrial complexes in Scranton during the city’s more prosperous years was the Scranton Lace Works. The large central clock tower of this cluster of industrial buildings dominated this part of the city. From its inception in 1897, it became the image of what was the first — and at one time the largest — manufacturer of Nottingham Lace in America, using cast iron-framed looms imported from England that were more than 50 feet long and two and a half stories tall. The company employed as many as 1,400 people at the height of its operation, and featured a theatre, bowling alley, gymnasium, infirmary, the clock tower with a Meneely cast iron bell and other amenities for the employees (fig. 6).

The factory complex was abandoned in 2002 after the company went bankrupt, and much of it was torn down in 2018 to make way for the construction of a mixed-use development of townhouse apartments and commercial space to be known as Laceworks Village (fig. 7). In an effort to preserve some of its iconic elements, the new project will incorporate the clocktower and a portion of the original factory that will be renovated into apartments. As people from the neighbourhood gathered to watch the buildings come down, one said: «When my dad returned from World War II, he was an accountant, my mother was a secretary, and they met here. My mother gave my dad one look and she said, this is the man I'm going to marry», since the old Factory reminded him of his parents in their younger days. Another who lived across the street said: «I can still hear the looms at night. If only I could imitate the sound… But it didn't keep you up at night, because you just got used to it» (Lange 2018).

The collective memory of historic downtown Scranton has been lost through the neglect and the failure to preserve the iconic buildings and the communities linked to those urban structures. The new city dynamics of the city has socially isolated its residents since there is no more walking culture within those blocks of the city.

Conclusions

It is evident that places and buildings are related with memories, constructed individually or collectively. These intangible links between the environment, natural or built, do not elevate the preservation of a part of the heritage to being an act of interpretation, as Lucia Allais states in his book (Allais 2018: 29). Recognizing that memories are attached to places does not make the architectural or natural objects relevant solely by being part of their individual or collective imagery, perhaps with the intent to democratize their historical value as memories of the common people. Choices as to whether to conserve or demolish, preserve or destroy have been made for a very long time while ignoring these attachments between the environment and its inhabitants. The nature of their intangibility has made them invisible to the eyes of those global forces of modernity, and even to those who have the intent of recovering the past.

As Professor Loughlin Kealy stated during the EAAE VII Workshop on Conservation hosted in Prague during the fall of 2019, «Conservation deals with how we extend the life of things» (Kealy 2019) [2], in other words, how do we keep things alive. Our memories play an important role in our lives, and through human experience, memories are constructed through an intense compromise with time. They are continuously nurtured by those invisible links, and they do not just imply a nostalgia for the past. They live within the modernity, they live within us, and to keep them alive we must conserve those tangible and intangible values of our heritage because of their undeniable ability to continue to create memories.

From Haussmann’s demolitions and reconstructions in the city of Paris, to Robert Moses’s wrecking ball and bulldozer removals of whole in New York City blocks, and to the destruction of small enclaves that were part of the collective memory of historical events and communities, it is possible to recognize that there is continued interest in society in erasing some traces of our past that may want to be forgotten for the sake of contemporary news development. The destruction of these physical traces is an intrinsic problematic part of our relationship with the past, and it brings with it the threat of the effacement of the invisible attributes of our own culture.

Endnotes

[1] This letter was found by Professor Maria McDonald and graduate student Josh Berman in the archives of the Architectural Heritage Association of Scranton, and thanks to Glenna Lang who knew that the letter existed.

[2] This conversation was part of the Group 4 discussion on The Scale of New Intervention Versus Memory during the EAAE Workshop VII Conservation-Demolition, held in Prague, Czech Republic, 25-28 September 2019.

References

Allais, L. (2018). Designs of Destruction. The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth Century. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Bataille, G. (1988). The accursed Shared. Vol 1. New York, Zone Books.

Byles, J., 2005, Rubble. Unearthing the History of Demolition. New York.

Crinson, M. (2005). Urban Memory. City and Amnesia in the Modern City. New York, Routledge.

Fine, A. S., Lindberg, J., Wood, B. (2002). Protecting America’s Historic Neighborhoods: Taming the Tear Down Trend. Washington D.C., National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Halbwachs, M. (1990). On Collective Memory. Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

Jacobs, J. (1981). Letter to Mr. Tim McDowell, 31 December. Director of the Office of Economic and Community Development of the City of Scranton, PA.

Jacobs, J. (1992). The Death and Life of the Great American Cities. New York, Vintage Books.

Kealy, L. (2019). Conversation with Loughlin Kealy, 26 September.

Lange, S. (2018). ‘Saying Goodbye to The Scranton Lace Works’. WNEP Channel 16 News, Scranton, PA, 29 June. Available at: https://www.wnep.com/article/news/local/lackawanna-county/saying-goodbye-to-the-scranton-lace-works/523-641c2aca-75b0-49e0-9506-167be94cf9d3 (Accessed 16 March 2020).

Moncan, P. de, Heurteux, 2002, C. Le Paris d’Haussmann. Paris, Editions du Mécène.

NYT, Editorial. (1963). ‘Farewell to Penn Station’. The New York Times, 30 October.

Page, M. (1990). The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Ricoeur, P. (2004). Memory, History, Forgetting. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Rossi, A. (1984). The architecture of the city. Cambridge, Massachusetts, The MIT Press.

Rykwert, J. (2017). Remembering Places. A Memoir. New York, Routledge.

Salter, R. (1992) ‘Scranton Demolishes Buildings to Make Way for New Mall Buildings in Scranton Blown Up; $101 Million Mall to Rise from Rubble’. The Morning Call, 6 April. Available at: https://www.mcall.com/news/mc-xpm-1992-04-06-2863574-story.html (Accessed 15 February 2020).

The Scranton Board of Trade. (1912). Being an Illustrated and Descriptive Booklet of the City of Scranton, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Scranton.

Bibliography

§ Allais, Luci. Designs of Destruction. The Making of Monuments in the Twentieth Century. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2018.

§ Benton, Tim. Understanding Heritage and Memory. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2010.

§ Bergson, Henry. Matter and Memory. New York, Zone Books, 1991

§ Byles, Jeff. Rubble. Unearthing the History of Demolition. New York, Harmony Books, 2005.

§ Crinson, Mark. Urban Memory. City and Amnesia in the Modern City. New York, Routledge, 2005.

§ Cubitt, Geoffrey. History and Memory. Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2007.

§ Hadler, Mona. Destruction Rites. Ephemerality and Demolition in Postwar Visual Cultrure. London-New York, I.B. Tauris, 2017.

§ Halbwachs, Maurice. On Collective Memory. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990.

§ Moncan, Patrice de; Heurteux, Claude. Le Paris d’Haussmann. Paris, Editions du Mécène, 2002.

§ Page, Max. The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990.

§ Ricoeur, Paul. Memory, History, Forgetting. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2004.

§ Rykwert, Joseph. Remembering Places. A Memoir. New York, Routledge, 2017.